Richard was the third of five sons of King Henry II of England and Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine. He was known as Richard Cœur de Lion or Richard the Lionheart because of his reputation as a great military commander and brave warrior.

Richard was the third of five sons of King Henry II of England and Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine. He was known as Richard Cœur de Lion or Richard the Lionheart because of his reputation as a great military commander and brave warrior.

Brothers Richard and Geoffrey joined the side of Young Henry when Henry the Young King instigated rebellion against Henry II. They had the formidable backing of King Louis VII and the French barons. However Henry II raised an army to face the rebellion, defeating King Louis in the siege of Rouen battle and a peace Treaty of Montlouis was signed in September 1174. Henry II and Louis VII made a truce on 8 September 1174. When support fell away, the three brothers then had little choice but to seek their father’s forgiveness. The terms the three brothers accepted were less generous than those they had been offered earlier in the conflict. Richard was given control of two castles in Poitou and half the income of Aquitaine.

Richard became the eldest surviving son and therefore heir to the English crown on the death of Henry the Younger in 1183. Tension between father and son escalated. Richard allied himself against Father and brother with 22-year-old Philip II, the son of Eleanor’s ex-husband Louis VII by Adele of Champagne. Henry II planned to concede Aquitaine to his youngest son John, but Richard refused believing that Aquitaine was rightfully his and that John was unfit to take over the land once belonging to his mother.

In 1189 Richard attempted to take the throne of England for himself by joining Philip’s expedition against his father. On 4 July 1189, the forces of Richard and Philip defeated Henry’s army at Ballans. Henry, with John’s consent, agreed to name Richard his heir apparent. Two days later Henry II died in Chinon, and Richard the Lionheart succeeded him as King of England, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou.

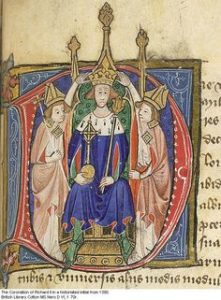

Richard I was officially invested as Duke of Normandy on 20 July 1189 and was crowned king in Westminster Abbey on 3 September 1189. The coronation was performed by Baldwin of Exeter, Archbishop of Canterbury. The ceremony was an elaborate affair, consisting of prayers and rites. Nineteen archbishops, bishops and bishops-elect, thirteen abbots (two from France), eleven earls, seventeen great barons and officials participated.

Richard I was officially invested as Duke of Normandy on 20 July 1189 and was crowned king in Westminster Abbey on 3 September 1189. The coronation was performed by Baldwin of Exeter, Archbishop of Canterbury. The ceremony was an elaborate affair, consisting of prayers and rites. Nineteen archbishops, bishops and bishops-elect, thirteen abbots (two from France), eleven earls, seventeen great barons and officials participated.

The bishops, abbots, and large numbers of the clergy, wearing silken hoods, preceded by the cross, taper-bearers, censers, and holy water, as far as the door of the king’s inner chamber. They then escorted Richard to the church of Westminster, as far as the high altar. The procession was solemn, with chants of praise.

First came the clergy in their robes, carrying holy water, and the cross, tapers, and censers. Next came the priors, then the abbots, and then the bishops, in the midst of whom walked four barons, bearing four candlesticks of gold, then Godfrey the Luci carried the royal cope alongside John Marshall who carried two large and heavy spurs from the king’s treasure, then William Marshall carried the royal sceptre which was topped with a golden design of the cross alongside William earl of Salisbury who carried the royal rod topped with dove. Three other Earls followed (David, earl of Huntingdon, John, earl of Mortaigne and Robert, earl of Leicester) carrying swords with golden sheath swords from the king’s treasure. Sword-bearing before the monarch was a mark of signal honour at this time.

Next came six earls and six barons, carrying on their shoulders a very large chequer board, on which were placed the royal arms and robes; and after them William de Mandeville, earl of Aumarle and earl of Essex, carrying a great and massive crown of gold, decorated on every side with precious stones.

Richard was assisted by Hugh, bishop of Durham on his right, and Reginald bishop of Bath on his left. Four barons held a canopy of silk on four lofty spears over them. A number of earls, barons, knights, and others, both clergy and laity dressed in their robes followed. The procession entered with Richard, and proceeded as far as the choir. Richard then arrived at the altar and made three oaths to the archbishops, bishops, earls, barons, clergy and people. He swore on the Gospels and on the holy relics that he would exercise true justice and equity towards the people committed to his charge. He also swore that he would abrogate bad laws and -unjust customs, if any such had been introduced into his kingdom, and would enact good laws, and observe the same without fraud or evil intent.

After having been stripped of his clothes and left only in his shirt (unstitched at the shoulder) and breeches, Richard was shod with sandals woven from gold. Then he was anointed as king by Baldwin, archbishop of Canterbury. This was done by pouring holy oil over Richard ‘on three parts of his body, namely on his head, on his shoulders and on his right arm, with the appointed prayers for this act’.

Then consecrated linen and the cope over it were placed on Richard’s head and he was dressed in the ceremonial robes: a tunic and a dalmatic. Afterwards the archbishop girded him with a sword “for constraining those who do wrong to the Church” and protect the weak. Then he received the splendid golden spurs and was dressed in the cloak, and promised again that ‘with God’s help everything he had said before would be upheld in good faith’. Finally the crown he picked up himself and handed to the Archbishop was placed on his head and he was lead to his throne by Hugh bishop of Durham on his right and Reginald bishop of Bath on his left. Then he received the sceptre to hold in his right and the royal rod in his left hand from the Archbishop.

The king was led back to his seat by the bishops of Durham and Bath, preceded by those that had carried the articles of royal regalia. The Lords mass commenced, and, when they came to the offertory, Richard was led him to the altar by the bishops, where he offered one mark of the purest gold after which, the bishops led him back to his seat. The mass having been concluded, and all things solemnly performed, the two bishops, one on the right hand the other on the left, led him back from the church to his chamber, crowned, and carrying a sceptre in his right hand and the rod of royalty in his left, the procession going in the same order as before. Then the procession returned to the choir, and Richard took his royal crown and robes of royalty, and put on a crown and robes that were lighter; and, thus crowned, went to dine; on which the archbishops and bishops took their seats with him at the table, each according to his rank and dignity. The earls and barons also served in the king’s palace, according to their several dignities; while the citizens of London served in the cellars, and the citizens of Winchester in the kitchen.

The king was led back to his seat by the bishops of Durham and Bath, preceded by those that had carried the articles of royal regalia. The Lords mass commenced, and, when they came to the offertory, Richard was led him to the altar by the bishops, where he offered one mark of the purest gold after which, the bishops led him back to his seat. The mass having been concluded, and all things solemnly performed, the two bishops, one on the right hand the other on the left, led him back from the church to his chamber, crowned, and carrying a sceptre in his right hand and the rod of royalty in his left, the procession going in the same order as before. Then the procession returned to the choir, and Richard took his royal crown and robes of royalty, and put on a crown and robes that were lighter; and, thus crowned, went to dine; on which the archbishops and bishops took their seats with him at the table, each according to his rank and dignity. The earls and barons also served in the king’s palace, according to their several dignities; while the citizens of London served in the cellars, and the citizens of Winchester in the kitchen.

The lavish banquet that followed included 1,770 pitchers, 900 cups and 5,050 dishes. It was also an occasion to exchange the gifs. The freshly crowned king, for instance, gave the archbishop of Canterbury a huge ivory horn, that the archbishop chose to dispatch to the shire of St Thomas, Canterbury. It is believed that the first piece of music composed especially for a coronation to honour the new King was played at the festivities.

However, not everything ran smoothly that day. Richard barred all Jews and women from the investiture, but some Jewish leaders arrived to present gifts for the new king. Richard’s courtiers stripped and flogged the Jews, then flung them out of court. Rumours spread that Richard had ordered all Jews to be killed. The people of London believing this to be true attacked the Jewish population. Many Jewish homes were burned down, and several Jews were forcibly baptised. Some sought sanctuary in the Tower of London, and others managed to escape. Richard punished the perpetrators and ordered the execution of those responsible for the murderous rampage and persecutions, including rioters who had accidentally burned down Christian homes. He allowed a forcibly converted Jew to return to his native religion and distributed a royal writ demanding that the Jews be left alone.

Richard married Berengaria of Navarre, first-born daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre on 12 May 1191 in Cyprus after his conquest of the island. The wedding took place in Limassol at the Chapel of St. George and was attended by Richard’s sister Joan, whom he had brought from Sicily. She was crowned the same day by the Archbishop of Bordeaux and Bishops of Évreux and Bayonne.